Ireland is continually held up as the poster-child for austerity-driven 'aid' and how the European Union can successfully manage an economy through a depression with no real pain for bankers. Unfortunately, as we have pointed out previously, judging a nation's progress on the back of its bond yields (when liquidity is negligible and the mighty hand of ECB-collateral-reacharound is upon us) should become anathema from any serious analysis. The sad truth, specific to Ireland in this case, is the relative size and importance of EU subsidies (and the EU budgetary allocation) mean that assumptions of current account surplus going forward (the much-needed elixir to sustain the gross debt load the nation's taxpayers now are buried under thanks to banker-transfers) leave Ireland's debt sustainability greatly in question.

Authored by Dr. Constantin Gurdgiev, originally posted at True Economics blog,

There's been some debate recently as to the size and importance of EU subsidies to Ireland and the EU budgetary allocation in the context of Irish economic growth. Here are the facts.

First up, the summary of EU subsidies, contributions and net subsidies:

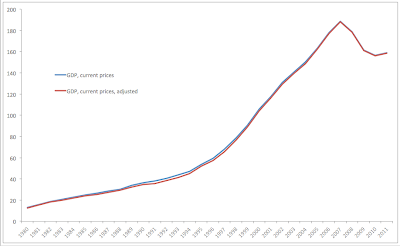

Next, using the IMF WEO database, the netting of the EU Net Receipts out of of our GDP and GDP per capita:

Factoring in the net receipts into growth equation:

The above clearly shows that lower volatility in receipts has contributed to smoothing of the GDP growth rates in most periods, but exacerbated 1991 and 2001-2002 slowdowns. EU net receipts also helped fuel (not significantly, though) 2004-2006 bubble and failed to provide any support for the economy in 2008-2010 collapse.

The reason for small effect of supports in recent years is very clear from the charts below:

However, the most dramatic effect the subsidies had was registered on the side of our external balance.

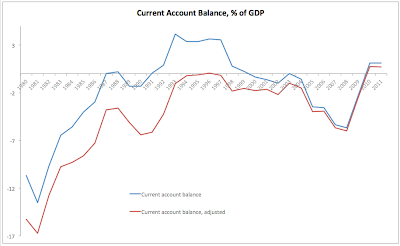

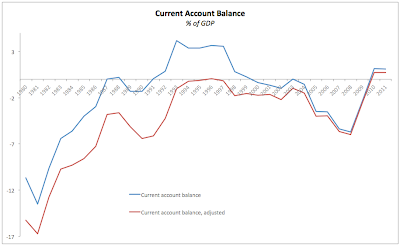

Recall that international 'experts' love the idea of Irish Current Account surpluses as the driver for sustainability of our debt. Herein, however, rests the problem:

The logic of 'experts' arguments is that Ireland can sustain current levels of Government debt because we have potential to generate current account surpluses vis-a-vis the rest of the world. And their evidence of that rests on their reading of past (1991-1999) current account positions.

Alas, once we net out net transfers from EU from these... the picture changes.

In the entire pre-2010 history, Ireland generated current account surplus (net of EU subsidies) in only one year, namely 1996. When one realises that debt sustainability for Ireland requires current account surpluses to be in excess of 3% on average over the next 10-15 years, one has to be slightly concerned by the prospect (as 2014-on suggests under the current EU Budget proposals) that Ireland will no longer be a net recipient of EU subsidies.

Here's what happens were Ireland to become net contributor to the EU budget in 2014-on at a rate of 1/2 of 2009-2011 annual subsidy received. Our average annual CA surplus (per IMF projections for 2013-2017) should run at 3.585% of GDP, but factoring in EU potential budgetary changes it is likely to run at 2.825% of GDP. And since the path of the CA surpluses is expected to decline (as IMF projects) in 2016-2017, then it is unlikely that the CA surpluses will be in excess of 3% over the period through 2022.

So what about that 'sustainability' of Irish debt levels, then?

UPDATE: And extended for those who initially questioned the analysis and were looking for more depth - the following is hard to question (and tough to swallow the assumptions that 'save' Ireland)

(via True Economics): Irish Current Account And Government Debt

In the previous post I highlighted the problem presented by the EU Budget changes in the near future to the sustainability of Irish debt dynamics. I referenced expert opinions on the role of current account surpluses in determining these dynamics. here is an example from early 2011 (emphasis is mine):

"... this dependency [2010 bailout] of Ireland on foreign support is difficult to understand given that the country has not lived continuously above its means in the past. Ireland has run a current account deficit (which means the country uses more resources than it produces) only for a few years; and if one totals the current account balances over the last 25 years, one arrives at a foreign debt of about €30 billion.

This should not be too difficult to finance given that it represents only about 20% of the country’s GDP of €150 billion. Moreover, Ireland is on track to run a current surplus this year and should thus not have any need for additional foreign funds."

Here's a problem - the above, as I noted in the previous post is based on some rather unpleasantly non-sustainable assumptions. Here's the arithmetic, based on IMF WEO data.

As chart above shows, Irish cumulated current account balances for the period 1980-2009 totalled -€39 billion, that's where the 'about €30 billion' miracle figure coming from. Alas, over the same period of time, Ireland received €39.4 billion worth of net transfers from the EU, which counted as a positive addition to the current account. Netting these out, Irish real 'external balance' cumulative for 1980-2009 was -€78.4 billion. Worse than that, net of EU subsidies, Ireland have run external deficits in every decade from 1980 through 2009. In other words, using the expert turn of phrase, Ireland used more resources than it produced in every decade through 2009.Now, was it true that Ireland 'has run a current account deficit only for a few years'? Why, here's a chart plotting Ireland's current account balances:Gross of EU transfers, Ireland run current account deficits in 1980-1986, 1989-1990, and 2000-2009, which means that it run deficits over 19 out of 30 years between 1980 and 2009, which is more than 63% of the time. Ireland run current account deficits almost 58% of the time in the period of 1980-2012. Hardly 'a few years'. More importantly, removing EU net subsidies, Ireland has managed to run current account deficits every year between 1980 and 2012 except in 1996 and 2010-2012. That means that Ireland was using more resources than it produced in 29 out of 33 years since 1980, or 88% of the time.For the last bit, let us recall that back in the 1990s (the period of Ireland's rapid recovery from debt overhang of the 1980s) Irish current account surpluses relative to General Government Debt stood at 26.8% (using 1999 level of General Government Debt and the cumulated current account surpluses, inclusive of EU transfers throughout the decade of 1990-1999). For the period of 2010-2017, the IMF projections imply the same ratio of less than 17.5%.Let's take a closer look at these comparatives. Irish debt peaked (for 1980-1999 period) in 1987 at 109.24% of GDP and was deflated on foot of a current account surpluses cumulated at 26.8% ratio to 1999 debt trough. For the period of 2000-2017, the debt will peak at 119.31% of GDP in 2013 and is expected to deflate at a maximum surplus rate of 17.5% (all based on IMF projections) before we allow for EU budgetary reductions for 2014-2022 period (which can bring this number closer to 14%).

- The 1990s exports boom driven by a combination of very robust US and UK growth expansions during the 1990s;

- The 1990s convergence race for Ireland to catch up with the EU capital and income levels - something that is now firmly exhausted as the potential for growth; and

- Significant net transfers from the EU during the 1987-1999 period that totalled some €12.6 billion which in 2014-2022 are likely to turn into net contributions to the EU from Ireland.