Submitted by Charles Hugh-Smith of Of Two Minds blog,

Peak Housing reflects not just a credit bubble but Peak Fraud and Peak Suburbia.

Once again pundits are claiming that housing is "finally recovering." But they're overlooking three peaks: Peak Housing, Peak Financial Fraud, and Peak Suburbia, all of which suggest years of stagnation and decline, not "recovery."

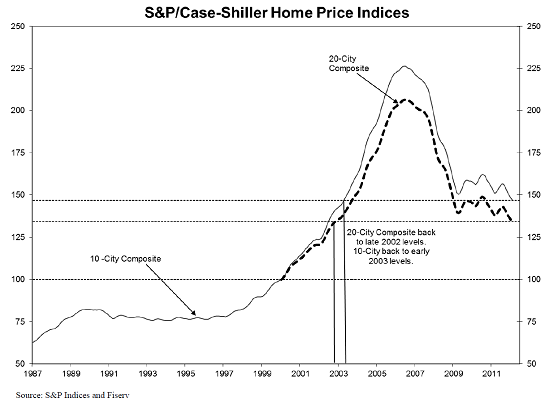

Here is the latest Case-Shiller index, which has traced out a nearly textbook bubble and a return to the mean that has been artificially restrained by trillions of dollars of Federal subsidies and backstopping of the housing market:

Here is a classic bubble and pop. Note that the "recovery" to bubble heights never arrived:

12 years later, the NASDAQ is around 3,000. If we adjust that by the 33% inflation since 2000 calculated by the BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics), then the NAZ is around 40% of the 2000 peak.

Note that there were several "recoveries" that fizzled before the index finally round-tripped to pre-bubble prices. On the Case-Shiller, that suggests an eventual drop from 130 to 75, the pre-bubble level.

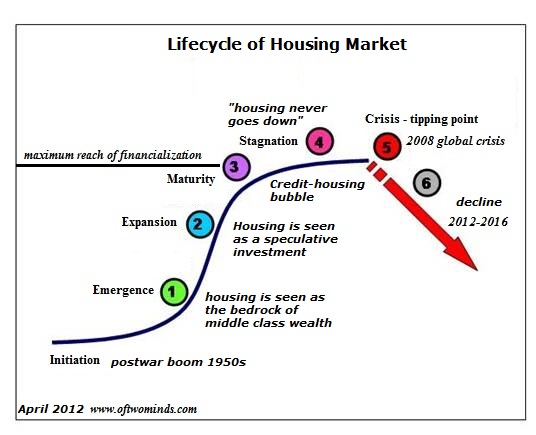

Like all other systems that have run their course, housing follows an S-curve.

After the vaporization of assets and cash in the Great Depression, America had largely reverted to a nation of renters. The postwar boom of plentiful jobs, cheap, government-guaranteed VA mortgages and virgin flat land near cities combined to fuel a suburban housing boom.

By the 1960s, the belief that housing was the bedrock of middle class wealth was firmly established. This was the explanation and motivation for buying a home: "housing never declines," and a rapid rate of household formation made it easy to sell a house to somebody else.

The high inflation of the 1970s and subsequent leap in housing prices embedded another key concept in the national psyche: housing wasn't just a forced savings plan that doubled as shelter, it was the speculative road to riches.

The mini-bubble of the late 1980s popped, sending housing into a six-year slump, but Peak Financialization and Peak Financial Fraud arose to goose housing to a new and spectacular credit-fueled bubble of frenzied speculation.

That systemic fraud was a key dynamic of the housing bubble is undeniable: everyone from those buying houses with no-document loans to money-center banks selling fraudulent mortgage-backed securities was relying on fraud. Peak Fraud isn't a necessary feature of financial bubbles, but it is often a causal factor among others.

If you have any doubt that the Crash of 1929 was accompanied by Peak Financial Fraud, I invite you to read John Kenneth Galbraith's The Great Crash 1929.

Alas, all bubbles pop, and now the world has changed. The overt fraud has been driven underground, but the repercussions of the institutionalized fraud of MERS and mortgage-backed securities hasn't been resolved; it remains in the market's blood stream, slowly poisoning what's left of the private mortgage market.

Peak Fraud will not be returning to the housing market, but its toxic consequences linger in the system. Does anyone seriously think the 4.4 million home equity lines of credit loans (HELOCs) on lenders' books are priced at their true market value? Accounting fraud in the form of overstated mortgage valuations is still rampant, and everyone knows it.

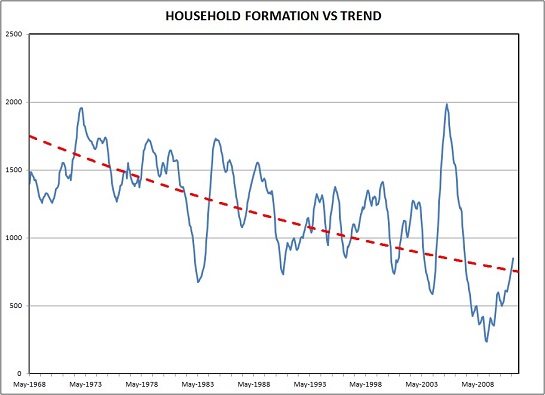

The rapid household formation of the 1950s and 60s period has given way to a generational decline. When housing, credit and oil were all cheap and plentiful, single people could buy condos and homes themselves, even with modest incomes. Credit may be cheap but housing and oil are not, and inflation has ravaged incomes, as noted here many times.

The demographics simply don't support rapid household formation; household formation is following an S-curve, too.

Then there's Peak Suburbia and Peak Commuting to Distant Exurban McMansions.

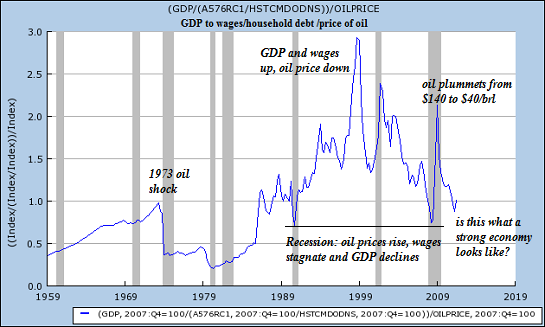

Here is a chart that correlates GDP (gross domestic product), the broad measure of economic growth and prosperity, with the price of oil and wages. Note that rising oil costs and stagnant wages take the wind out of the economy's sails.

Simply put, declining wages and high oil prices erode households' ability and willingness to buy a surburban home and pay for the gasoline needed to commute hundreds of miles every week.

Declining gasoline consumption is not an outlier, it is also a generational shift.

Mish recently addressed this dynamic: Demographics and Changing Social Trends Behind Gasoline Sales Plunge, and I covered the long-term trends in Why Is Gasoline Consumption Tanking? (February 10, 2012)

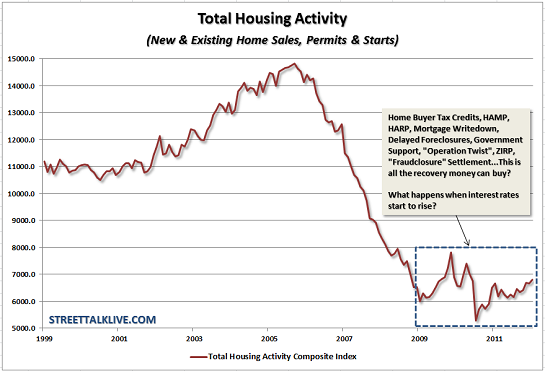

Once the belief that housing is the bedrock of middle class wealth fades, so too will the motivation to risk homeownership in an economy that puts a premium on mobility and frequent changes of careers and jobs. We can discern a sea-change in this chart of housing activity: despite trillions of dollars in subsidies, guaranteed mortgages and other types of Federal support, the housing market has not recovered, it has only stopped plummeting:

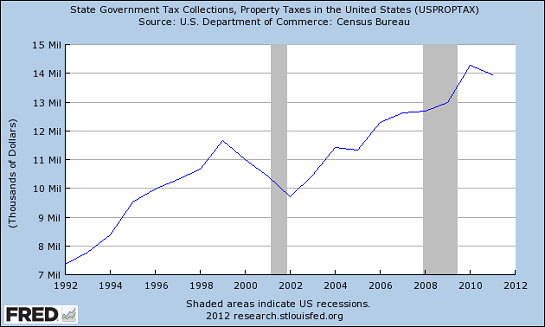

Only one aspect of housing hasn't yet peaked: property taxes. If the risks of homeownership weren't apparent before, they certainly are now as local governments jack up property taxes to indenture homeowners into tax donkeys.

Note that property taxes declined significantly in the previous recession (2000-2002), but they rose steeply in the 2008-9 recession, and continued climbing. The recent modest slippage may have several factors: lower valuations in states that set property taxes on assessed values, tax revenues declining as homes in foreclosure languish with unpaid property taxes, and so on.

Anyone claiming that property taxes have peaked will have to support that claim with evidence that local governments have found other sources of tax revenues to replace property taxes. Until that dynamic changes, then local government will have every incentive to jack up property taxes by any and all means available.